The old, yellowing photographs all look remarkably similar: the centrepiece is mostly a line-up of musicians behind one or two towers of synths and a crowd pushing up in front of them or squeezing into whatever gaps it can find. It is almost always a big crowd, be it a sweaty horde in some concert hall in deepest Saxony; spilling out from the packed auditorium of Berlin’s Palace of the Republic; or perhaps a sea of faces flooding from between the monumental Stalin-era buildings on Strausberger Platz in the former capital of the GDR. If these old photos are telling the truth then all of these were big events, some of them very big indeed. From the early 1980s onwards, live performances of electronic music were pretty sure to attract masses of people, masses who presumably wanted to dream and be blown away.

The country in which these masses lived must surely have felt rather limited, circumscribed as it was by impenetrable borders. How large, wide, and infinite the cosmos stretching above it seemed in comparison! Musicians and fans therefore began one day to flee this limited country for the endless reaches of outer space. Not in reality, of course, for Soviet »Energia« brand rockets and »Soyuz« spacecraft were hard to come by. Synthesisers, drum computers, and samplers were their means of flight and it was these which gave rise to the GDR’s whimsical, dreamy, expansive electronic pop music, and allowed musicians and their listeners to escape »real-socialism« for wildly pulsating fantasy landscapes and the infinite realms of far-flung galaxies – or at times simply the palpable pleasures of a local disco that nonetheless appeared to be on a space station circumnavigating planet earth on a geo-stationary circuit.

The East German scene that produced such music from the early 1980s onwards was very limited. Yet the circa twenty synthesiser geeks who belonged to it were all pros with impeccable musical training: Reinhard Lakomy, for instance, sadly deceased in spring 2013, was renowned above all for rock albums and recordings for children. Then there were bands called Pond, Key, Servi, or the like, which have mostly since sunk into oblivion. And even paragon rock band The Puhdys couldn’t resist releasing an electro pop album in 1982: Computerkarierre (Computer Career), a crossover of experimental synth instrumentals and Neue Deutsche Welle (aka New German Wave or NDW). Between 1981 and the demise of the GDR nine years later, East German electro musicians released around a dozen albums in total, mostly solo endeavours.

But this small scene had nothing in common with the academic electronic-electroacoustic contemporary music being explored at the time in the studios of radio stations and universities throughout East and West Germany, nor with the experimental, electronica-influenced underground sounds produced from the mid-1980s onwards by »anderen Bands« (»the other bands,« a term that referred to alternative bands of 1980s GDR) such as AG Geige, Sandow, and Ornament & Verbrechen. Electronic pop musicians’ role models were neither Stockhausen nor Einstürzende Neubauten but rather Vangelis, Jean Michel Jarre, Ash Ra Tempel, and Klaus Schulze, at times also Genesis, Pink Floyd, Emerson, Lake and Palmer, and, first and foremost, Tangerine Dream. »I watched Western TV in secret just like any other guy and sometime in the mid-1970s I saw a show that featured Tangerine Dream making music in a castle in England,« Reinhard Lakomy told me when we met in 2010. »Sounds, rhythms, and sequences such as I had never heard before. It just blew my mind.« Lakomy, born in 1946, was already a successful musician in the GDR at the time – and in 1981 he became the first to release an album of electronic music: Das geheime Leben (The Secret Life).

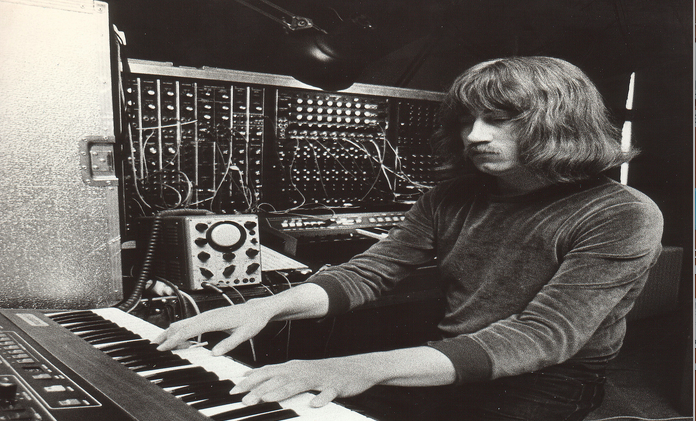

The West Berlin electronic band Tangerine Dream had accepted an invitation from DT64, East Germany’s radio station »for young people,« to play live in East Berlin’s Palace of the Republic on 31 January 1980 – the first West German pop band ever to do so. Many of the electronic musicians who later enjoyed success in the GDR were there that night, as fascinated as they were inspired. »Tangerine Dream didn’t use lyrics actually, so the band initially seemed apolitical – I think that’s why they were allowed to play in the East at all,« muses Wolfgang »Paule« Fuchs, who was born in Berlin-Prenzlauer Berg in 1948, and became the most commercially successful electronic musician in the GDR thanks to his Pond project. »Then I came across a photo of Klaus Schulze seated on the ground, dressed in a space suit and helmet, and completely surrounded by keyboards. ›Wow!‹ I thought. ›We’ll do that too.‹«

On the trip… but behind the times

When Tangerine Dream played the Palace of the Republic in 1980 many East German musicians were already vaguely familiar with cosmic music and krautrock, genres that musicians in West Germany had been exploring throughout the previous decade. Although officially prohibited from listening to Western Radio most of them tuned in regularly to West Berlin shows, such as »Steckdose« (subtitled »Computer Music – Music Computer«), which featured interviews with Tangerine Dream or Klaus Schulze and presented new synthesisers and other novel gadgets. Bootleg cassette recordings circulated »underground.« Then in 1986 the youth radio station DT64 began broadcasting its »Electronics« programme and organising live music festivals. Thus East Germans could at last follow the scene quite legally. It must be added, of course, that when Tangerine Dream played in the GDR and so inspired East German musicians, the band’s heyday and that of its musical genre were practically over in the West. East Germans were behind the times when it came to the electronic trip because the »real-socialist« regime strictly controlled cultural production and had branded electronic music »inhumane.« But sometime in the early 1980s the powers-that-be decreed that the future lay in »Kleincomputer« (microcomputers) – and therefore gave the green light for the music these were able to generate, which at the time did indeed sound futuristic.

East Germans were behind the times when it came to the electronic trip because the »real-socialist« regime strictly controlled cultural production and had branded electronic music »inhumane.«

However, this didn’t mean that just any GDR citizen could now launch a DIY freelance career, recording, releasing, and performing electronic music. A permit from the state was still required. Julius Krebs, who was born in 1954 and gave solo performances of his project JSE (Julius Krebs – Sinfonische Elektronik) in East Germany, says: »there were two kinds of pop musician in the GDR – amateurs and professionals. Both first had to demonstrate some talent and were only then given a permit to perform, a permit that also specified the hourly rate they could earn. Without a permit one couldn’t even grab a guitar and play on the street. That was strictly forbidden.« A commission examined an artist’s musical skills, lyrics, appearance, and repertoire. And anyone who intended to earn a living as a professional musician needed a further special license. »In the West, lots of electronic musicians tinkered about in their home studios,« says Hans-Hasso Stamer, who was born in 1950, studied computer science in East Germany, and spent his student days building synths and pimping Western equipment with which he then performed live. »It was different in the GDR. Anyone who hadn’t officially studied music but wanted to release something on vinyl first had to play for years so as to prove his or her skills and reliability. So there was no greater accolade than to finally be allowed to release an LP.«

Only one state label existed in the GDR for LP releases in the popular music sector, namely Amiga, which was operated by the »People’s Own Enterprise« (VEB) Deutsche Schallplatten Berlin. No one other than selected musicians was allowed to publish LPs, and these always retailed, moreover, at the uniform price of 16.10 Ostmark. Production material was in short supply and this limited both the frequency and number of releases. »But sales didn’t matter a damn in the GDR, to be honest,« explains musician Rainer Oleak, who was born in 1953 and collaborated with Reinhard Lakomy on the electronic LP Zeiten (Times) in 1985. »A lot of stuff didn’t sell well for the simple reason that too few copies were available. But in any case, most musicians made their living from live gigs.«

Masters of hidden meanings

Although record releases in the GDR were subject to censorship, the electronic music discussed here was generally purely instrumental and therefore unproblematic in this regard at least. Yet many of the records may nonetheless have conveyed hidden meanings – East German artists were not infrequently masters of this art. For example, in 1983 Reinhard Lakomy named his second electronic music LP Der Traum von Asgard (The Dream of Asgard), with liner notes that rambled on about how »One used to say Asgard, by which one meant unlimited freedom in simultaneous comfort, meant love without hate, meant permanent abundance.« The lyrics hence possibly referred to the »Golden West« so longed for by many citizens of the GDR. Yet whoever took a closer look was able to see that »the points of the golden spears are bent, the panelled floors full of stains, and the precious gems no longer in their settings.« The West was not as golden as it was made out to be, after all. And one track on Lakomy’s first album is titled: »Es wächst das Gras nicht über alles« (Some things one never gets over). Is this perhaps a subtle political statement? »Nonsense!« replied Lakomy in a booming voice, as self-assured as ever when I asked him shortly before his death. »It’s simply an eternal truth.« Yet most other members of the electronics scene lower their voices even today when talking about being under surveillance by the East German secret police – the dreaded »Stasi« – or about other repressive measures taken back then by the state such as censorship, for example, which musicians to this day call »proofreading.«

These were obstacles faced also by the musical duo Servi, for example, which had first seen the light of day in 1975 as a Christian rock band and eventually switched to performing meditative ambient music in churches. »Church work was always a means to oppose the ruling regime,« says Jan Bilk, born in 1958 and one half of Servi. »We were a church band at the time. We played every weekend in various parishes, giving concerts of meditative electronic music as well as accompanying church services on Sunday mornings. We had to play quietly and without drums. We didn’t want grandmas, keeling over in the pews. For that reason, but also because we lacked the energy at some point to engage in endless discussions about our lyrics, we began doing purely instrumental stuff in 1982.« According to Bilk, Servi was never aware of being subject to repression – everything ran normally. »Yet: What is normal,« he asks now. »We had nothing with which to compare our experience, and therefore no idea of how different things might be elsewhere. All we knew was that there was a wall somewhere, which put a limit to what we could do. For example, we often couldn’t get a permit when we wanted to play some place. We’d sit around in a bureaucrat’s office, usually for an hour or so, and then an official would turn up and hem and haw about some problem or other… And that would dash a whole year’s hopes in one go. It was like ubiquitous fog. For sure, fog won’t kill you, and you may even get along quite well in a fog; but fog seriously limits your vision.«

In 1986 Servi finally released its debut LP Rückkehr aus Ithaka (Return from Ithaka). It was the first ever sound carrier officially on sale in the GDR recorded not by the state but by a private producer. »Produced by SERVI« is clearly stated on the back of the album sleeve – and so it was a real sensation! The hand of the Church was protective at least in some respects, for it not only facilitated such new developments but also helped Servi get hold of equipment. Bilk’s memory of being handed a brand new Moog Prodigy compact synthesiser in Bautzen in eastern Saxony is still fresh in his mind today. A Jesuit priest had assembled a special collection in his parish in Cologne, and dispatched the equipment to Servi.

However, you still had to find someone who’d bring the equipment over the border for you. Many people demanded payment for that so a synthesiser could end up costing around 40 000 Ostmark. To put that in perspective, my mother earned 400 Ostmark a month back then.

Paul Fuchs

However, other East German electronic musicians had to scheme like mad in order to get hold of Japanese or American top-brand synthesisers or drum machines and smuggle them into the country. No one wanted to have to play the few local products available: the Tiracon 6V from the VEB Automatisierungsanlagen Cottbus (Automation Works Cottbus), for example, or the Vermona-brand equipment turned out by the VEB Klingenthaler Harmonikawerke. All such equipment was doomed to break down. But the (generally illegal) import of Western equipment could succeed only with the help either of fellow musicians in possession of a travel permit for performances abroad (so-called »travel cadres«), or of befriended old age pensioners (because retired East Germans were allowed to travel abroad), or through contact with Western journalists and diplomats. »To get hold of Western equipment one first had to raise the dough, i.e. to exchange Ostmark for hard currency…which was illegal, of course,« tells Paule Fuchs. »An exchange rate of one to six or seven was normal, but sometimes you’d get one to ten. And then you still had to find someone who’d bring the equipment over the border for you. Many people demanded payment for that so a synthesiser could end up costing around 40 000 Ostmark. To put that in perspective, my mother earned 400 Ostmark a month back then.«

Fuchs’ colleague Julius Krebs can still remember how the Chinese wife of a member of one of his early bands held a passport that enabled her to cross the border into West Berlin every day. The couple thus managed to import numerous pieces of equipment and this was how Krebs himself acquired some of his gadgets. »As far as I know I was the first person in the GDR to ever own a Commodore C64 and to play a Roland TB-303 live on stage,« he recalls. »I used an old Soviet TV as a monitor for the C64. But those computers were terrible – they crashed constantly. One of them once crashed seven times during a single concert. Which means the monitor suddenly displayed nothing but hieroglyphs while the synths all emitted the same single note. What does one do then? Well, one plays on manually while discreetly rebooting the computer! That fascinated people actually, because they could see the amount of work it took. They too could feel the tension – and they knew the sounds were being created, calculated, at that very moment.«

Wary of the playful appropriation of signs and codes

The records released under these adverse conditions between 1981 and 1990 do not belong to any canon of electronic music. They are an almost forgotten branch on the evolutionary tree of electronic music – and yet a branch on which a few obscure but wonderful sounds once blossomed. They amount to a string of skilful thefts, daring ideas, beautiful coincidences, and pretty misunderstandings. A selection of these releases can be found, for example, on the compilation Mandarinenträume – Electronic Escapes from the German Democratic Republic 1981–89, released in 2010 on the Munich label Permanent Vacation. It features endless synthesiser epics that seem to tell of trips to far-flung galaxies as well as ambient tracks that conjure dreams of nudist beaches on the Baltic Coast. One also finds disco tracks drenched in the heartbreaking pathos of electric guitar solos, as well as weird and wonderful forms of cosmic disco, despite the fact that none of the musicians involved had ever spent time on the shores of Lake Garda in Italy, where the latter genre originated. And the compilation also presents a prolific number of psychedelic krautrock jam sessions, which it is difficult to believe were created in the absence of drugs – although all participants swear by it. »We honestly didn’t have any drugs at all«, claims Fuchs. »I was part of that scene for aeons yet I cannot recall a single case. Where would anyone have gotten hold of drugs? All we had was alcohol.«

These records also hold an aesthetic surprise in store. Although produced in a country that heralded mechanical engineers and cosmonauts as heroes, and that was filled to the gills with an optimistic faith in technology – or rather in the interplay of personal diligence, science, and technology as a means to improve people’s lives and ultimately establish communism – the records contain no music that is emphatically reminiscent of machinery. Official LP production in the GDR thus bears no trace of the influence of Kraftwerk or of the industrial music of the period. The irony inherent to them and their playful appropriation of signs and codes likely made people wary.

A crass break

The »Wende« (political turnaround) that began in 1989 represented a crass break in the biographies of these electronic musicians and indeed of all citizens of the GDR. At times, not even a glimmer of public interest in Eastern bloc music persisted. »The events of 1989 and thereafter swept away everything that had ever had any value in the GDR, and everything we had ever held dear, and our biographies were all pretty much dismissed as inferior,« Reinhard Lakomy told me, with some resentment. Both professionally and privately, he and a very few of his colleagues survived the collapse of the regime under which they had grown up relatively well. But not everyone was so lucky. »During the Wende everything disappeared in a kind of maelstrom«, recalls Hans-Hasso Stamer. »Either one could find the energy to say, ›Ok, that’s that: time to start again from scratch‹ or one couldn’t. And I’ll tell you quite frankly: I couldn’t. For a while I did nothing but write poetry.«

Today, Stamer, Krebs, Fuchs, and those of their colleagues who are still alive, all live in or near Berlin. To visit them one has to head for the far reaches of the public transportation network, travel to the end of the lines, into the endless, peripheral, non-place landscapes comprised of motorway junctions and hardware stores, derelict industrial buildings in which every single window has been meticulously smashed, and rows of allotments enclosed by neatly trimmed hedges. For some of these musicians or ex-musicians, the recordings of electronic music from »way back when« are the most important thing they have ever accomplished in their lives – for others, only a small, almost embarrassing gaffe. Some of them make good money today. Others barely keep their heads above the water. Whatever the case, their history should not go untold.